10.2 ENGINE SYSTEM DESIGN INTEGRATION BY DYNAMIC ANALYSES

The Scope of Dynamic Analyses

Dynamic analyses are essential for optimum engine systems design integration, commensurate with vehicle mission requirements. Dynamic analyses may be grouped into two basic areas:

- Internal operating dyn an is of the engine system.-This refers to system schematic and control optimization, component optimization from a functional as well as system transient point of view, optimization of system start transients, minimization of cutoff impulse, determination of cutoff surges, etc.

- Engine-vehicle operating dynamics.-This refers to vehicle tank pressurization systems design for adequate transient and steady-state engine performance, engine-vehicie structure and engine-guidance operating compatibility and stability, overall vehicle performance during special maneuvers, etc.

Gsneral Approach to the Analyses

The techniques and equations used, and the general approach taken by industry and Government agencies toward the solution of the various dynamic problems in rocket engine systems, are the result of many years of effort and experience in the areas of analysis, synthesis, and correlation of rocket engine operation. The philosophy governing this approach postulates that the relevant characteristics of any system depend on the characteristics of their components and physical processes. By describing these components and processes in detail, as well as their interaction, the system can be described analytically with as much detail as is necessary. The complete set of equations then represents a mathematical model of the engine system.

Through the solution of the equations representing the mathematical model, the important characteristics of an engine system are studied, problem areas are defined, and improved component designs for the solution of these problems may be evaluated. Also, transient and steadystate engine systems operation, as affected by various component characteristics, may be simulated and checked by these dynamic analyses. If necessary, modifications will be incorporated prior to hardware testing.

Dynamic analyses, however, have their limitations, because not all of the physical processes involved in a given rocket engine system are immediately and/or thoroughly understood. As each of the processes becomes better defined functionally and quantitatively, confidence in the mathematical analyses increases.

Let us look at an example. The hydraulic head developed by a propellant pump is, as we know, a function of pump speed, flow rate, and geometry. We can write:

where pump developed head, ft pump speed, rpm pump flow rate, gpm pump impeller radius, in area normal to the meridional flow, in Correlations, such as equation (10-1), can be used to determine the interdependence of the many processes within an engine system. Furthermore, equation (10-1) may be expressed as a specific form of function, as shown by equation (10-2), which is valid for a particular pump design only.

When the numerical values of are known, equation (10-2) becomes a quantitative description of a given pump design and a means to obtain the numerical solution of the operation of an engine system.

Some physical processes, such as thrust chamber combustion dynamics, are not always quantitatively fully understood. Rate of combustion is known to be a function of pressure, propellant type, mixture ratio, and combustion chamber geometry, but a specific quantitative expression for reliable use with rocket engine combustion chambers is not available. Certain system-start-transient analyses made with the aid of an engine model (set of equations like eq. (10-2)) have ideally assumed instantaneous combustion. Thus, combustion instability or thrust-chamber-feed-line, system-coupled instability is not described. This deficiency can be rectified by experimental systems evaluation.

Dynamic analyses can also be effectively used during the development-redesign phase of an engine system. Once test information is available, the predicted characteristics (with idealized assumptions) and the actual system operating characteristics can be compared. Differences can be noted and evaluated. This testanalysis cycle defines the limits of component performance and thus serves as a guide for the redesign of the components to be integrated into an optimum, final engine system. Similarly, from analyses of the engine-vehicle operating dynamics, and in conjunction with test results, the engine system and its components can be modified and improved.

Criteria for the Mathematical Model of an Engine System

The mathematical model of an engine system generally consists of a group of lumped parameters, and of linear or nonlinear algebraic and differential equations, which are formulated and then programed for an analog or digital computer. Careful examination of an engine system schematic will be sufficient to determine whether a mathematical model will be possible for the system. This simply amounts to an observation of the many significant physical processes involved in the entire system which may be expressed mathematically. Some idealized assumptions are usually required to obtain a quantitative expression of the various equations. The physical significance of these assumptions must be understood before the mathematical model can become meaningful.

There are many ways to describe a rocket engine system mathematically. The choice will be based on the answers expected from the model. A model used to predict engine systems orificing requirements may call for high steadystate accuracy over a stated operating range, while the dynamic characteristics are of little consequence. A model used for the design integration of control components and subsystems may require good dynamic accuracy for intermediate frequencies ( cycles ) and good static accuracy. A model needed to describe high-frequency effects (100-10 000 cycles/ may require little in the way of static accuracy, since the phenomena under study occur so rapidly that the system as a whole has no time to shift to new operating levels.

The mathematical model most frequently used is of the type employed for system main-stage operation and control design. This usually serves as the basic mathematical model of an engine system, with some modifications incorporated for other, special applications. In general, all mathematical descriptions of a basic model are for conditions around the systems design point, with the following assumptions: (1) All liquid propellant flows are incompressible and at constant temperature (2) All gas equations are based on perfect gas performance, where the gas properties are functions of composition (3) All vehicle-supplied parameters, such as main propellant tank discharge pressures, are constant.

Examples of Equations for a Mathematical Engine Model

The mathematical expressions and equations for the various physical processes and operating dynamics of a rocket engine may be derived from equations given in chapter I and in other chapters for the design of the various components. Here, we will present several typical examples to illustrate the application of these equations in a mathematical model.

- Pressure drop of fluid flow in a duct or component:

where

- Combustion process and operating dynamics:

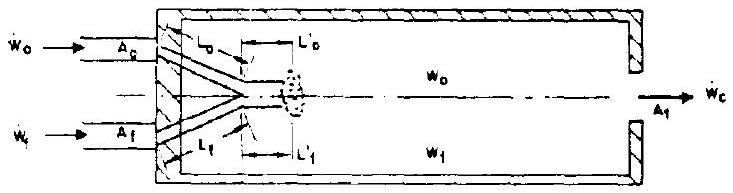

Refer to figure 10-2, which describes schematically the combustion process. A transportation time delay is assumed, representing the time required for the propellants to pass through the injector and enter into the combustion process. and expressed as

Figure 10-2.-Schematic description of the combustion process.

Figure 10-2.-Schematic description of the combustion process.

These can usually be indicated by the Laplace transformation operators and .If we assume a homogeneous combustion gas,we can define the following correlations:

where time required for oxidizer and fuel to pass through the injector and enter into the combustion process,sec density of oxidizer and fuel, injector area,oxidizer and fuel, travel distance of injected oxidizer and fuel prior to impingement,in travel distance of impinged oxidizer and fuel prior to combustion,in time period in consideration,sec injected flow rate of oxidizer and fuel,lb/sec weight of oxidizer and fuel stored in the combustion chamber volume,lb, at the beginning of time period weight of oxidizer and fuel stored in the combustion chamber volume,lb, at the end of time period =complex operator in a Laplace trans- formation pressure of the combustion gas,psia temperature of the combustion gas,

$V_{c} \quad=$ volume of combustion chamber from

injector to throat, in ${ }^{3}$

$R^{\prime} \quad=$ universal gas constant, $18528 \mathrm{in}-\mathrm{lb} /{ }^{\circ} \mathrm{R}$

mole

III =molecular weight of the combustion

gas, lb/mole

$w_{c} \quad=$ weight of the gas stored in the com-

bustion volume, lb

$\dot{w}_{c} \quad=$ flow rate of the gas emerging from the

combustion chamber, lb/sec

$R_{o} \quad=$ weight fraction of oxidizer stored in

the combustion chamber

$A_{t} \quad=$ throat area, $\mathrm{in}^{2}$

$g \quad=$ gravitational constant, $32.2 \mathrm{ft} / \mathrm{sec}^{2}$

C* = characteristic velocity, $\mathrm{ft} / \mathrm{sec}$

These equations for the combustion process can be applied to engine main thrust chambers,gas generators,and other types of combustor.

3.Turbopump operating dynamics:

Equation(10-25)is a torque-balanced equa- tion for turbopumps.Any unbalanced torque be- tween turbine and pump will initiate a change of shaft speed causing the integrand to seek zero. where pump inlet pressure, psia pump discharge pressure, psia a = pump pressure rise design factor, lb pump torque design factor, in-lb-sec pump impeller radius, in pump flow area, in density of the pumped fluid, pump shaft speed, rev/sec turbine shaft speed, rev/sec speed ratio of the turbopump gear train torque at pump shaft, in-lb torque at turbine shaft, in-lb turbine gas flow rate, available energy content of the turbine gas, Btu/lb turbine gas specific heat at constant pressure, turbine gas total temperature at inlet, turbine gas specific heat ratio turbine pressure ratio inertia of the gear train, referred to the main pump shaft, in-lb-sec nondimensional pump head coefficient nondimensional pump flow coefficient nondimensional pump torque coefficient pump overall efficiency turbine overall efficiency

Dynamic Analysis of Engine System Mainstage Operation

In general, engine design requirements at the mainstage level, as well as initial component and system specifications, can be determined with the aid of a mathematical model consisting of linearized descriptions of the complete engine system and a computer. Based on the static operating values at main stage (such as given in tables to ), the static design factors (such as and in eqs. 10-2, 10-3, 10-16, and 10-22) may be obtained. The primary dynamic analysis objectives for mainstage operation are: (1) Evaluation of the engine system schematic, with respect to mainstage operation (2) Evaluation of the dynamic characteristics, interactions, and the performance of various components at mainstage level.

This includes pressure drops in various flow passages, turbopump operating performance, and thrust chamber heat transfer and combustion characteristics (3) Optimization of engine system steadystate operation and performance, by properly calibrating and matching the design operating points of various components. (See sec. 10.3.) (4) Determination of engine system mainstage performance characteristics, including performance variations and engine influence coefficients. (See sec. 10.4.) (5) Evaluation of various engine control problems during main-stage operation, such as thrust and mixture ratio controls (6) Evaluation of various potential perturbations and their effects on mainstage operation Once the basic mathematical model for the main-stage operation of an engine system is established, it can be utilized to study special problems with additional inputs. For example, a basic mathematical description of the pound-thrust pump-fed rocket engine for an intermediate-range ballistic missile had been established on an analog computer. Following design of an additional engine-thrustcontrol subsystem, its electronics, main valves, and servovalve drive system were tied to an analog computer by suitable transducers to allow transient performance checkout and controller gain adjustment. An updated mathematical engine model, including the nonlinear perturbation, was then used for more detailed investigations of the thrust-control-loop dynamics.

Dynamic Analysis of Engine System Start and Cutoff Transients

The main objectives of dynamic analyses of engine system start transients are: (1) Investigation of the systems schematic for needed start-transient controls, such as type and quantity of control components, and sequencing and timing of their operation (2) Determination of thrust chamber ignition requirements (3) Estimation of start energy, time, and thrust buildup characteristics (4) Evaluation of component dynamic characteristics and interactions during start transients, such as combustion chamber ignition delays, gas generator temperature surges, and propellant pump stalling (5) Evaluation of system dynamic stability during the start transient. (The aim is to avoid prolonged operation at levels exhibiting system or thrust chamber instability.) (6) Evaluation of various potential perturbations and their effects on start transients, such as a start where the propellantsettling effects of gravitation are absent For some engine systems, such as the turbopump-feed A-2 stage engine, dynamic analyses of its start transient become rather complex. They may include effects such as water hammer (wave equation) in the propellant feed systems, distribution of heat transfers and pressure drops throughout the high-pressure fuel feed system, choking of hydrogen gas in the chamber coolant passages, stall characteristics of the fuel pump, cavitation at the pump inlets, changes in fuel density in the pump caused by enthalpy changes from pumping, and many others. Because of this complexity, the equations of these mathematical models are usually programed for a digital computer.

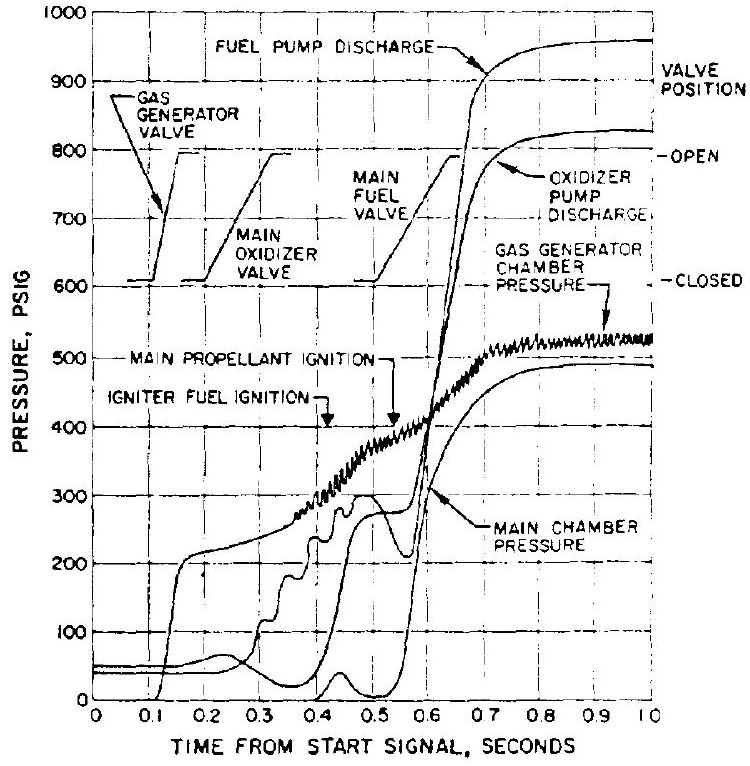

Figure 10-3 presents graphically the start transient model of a typical turbopump-feed engine system utilizing a gas generator for turbine drive. Valve timing, as well as pressure buildup characteristics of gas generator, propellant pumps, and main chamber are indicated. Other parameters, such as gas-generator combustiongas temperature and propellant flow rates, can be included in the model.

Several alternate engine-start methods are usually simulated with the start model, in order to evaluate potential problem areas and to optimize systems start transient operation.

Important objectives of dynamic analyses of engine cutoff transients are: (1) Investigation of the systems schematic for needed cutoff transient controls, including operational sequencing and timing of various control valves (2) Evaluation of pressure surges and other adverse effects in propellant ducts and feed system components during the cutoff transient

Figure 10-3.-Graphic presentation of the start transient model for a typical turbopump-feed engine system utilizing a gas generator for turbine drive.

Figure 10-3.-Graphic presentation of the start transient model for a typical turbopump-feed engine system utilizing a gas generator for turbine drive.

(3) Evaluation of possible temperature surges in main chamber or gas generator during the cutoff transient (4) Evaluation and optimization of total cutoff impulse, by minimizing cutoff time and improving repeatability (5) Evaluation of engine thrust decay characteristics A series of cutoff sequences with modified shutoff timing of the control valves is usually simulated with the mathematical model. The various simulated cutoff runs are then analyzed to determine potential problem areas, and whether these problems are a function of the particular sequence used.

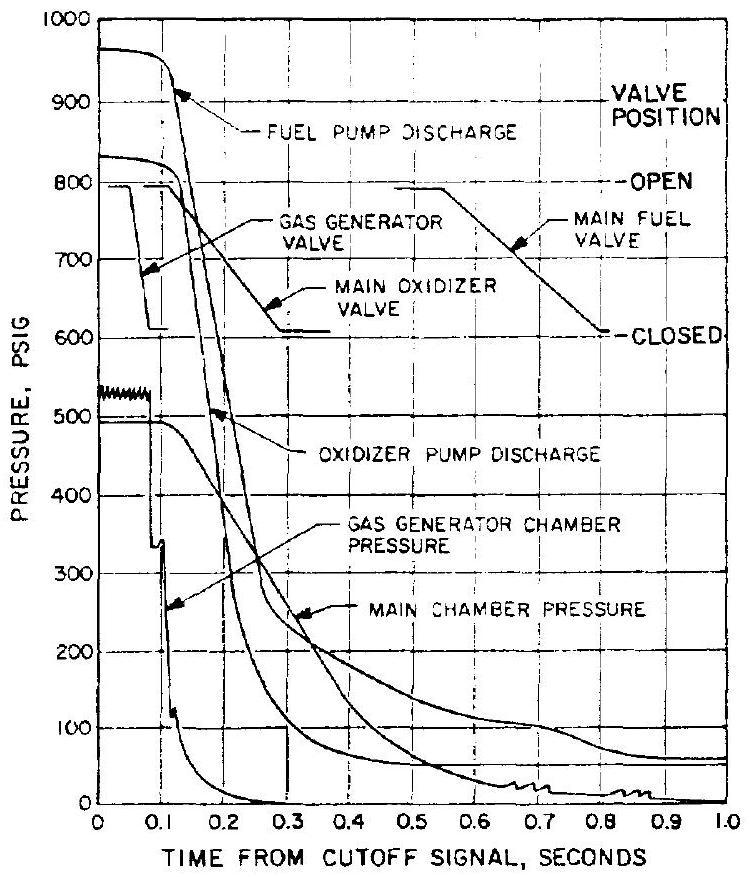

Figure 10-4 presents graphically the cutoff transient model of the typical engine of figure 10-3. The engine-thrust-decay characteristics are represented by the main chamber pressure decay curve. The integrated area under the chamber pressure versus time curve may be used to assess the engine cutoff impulse.

Dynamic Analysis of Engine-Vehicle Interactions

These analyses may be performed during the initial design phase of an engine system, as

Figure 10-4.-Graphic presentation of the cutoff transient model of the typical engine of figure 10-3.

Figure 10-4.-Graphic presentation of the cutoff transient model of the typical engine of figure 10-3.

well as following development test firings. Areas of general interest to be analyzed may include, but should not be limited to- (1) Engine system operation and performance requirements from a vehicle mission point of view (2) Matching of engine propellant supply requirements with the vehicle propellant system, including dynamic evaluation of the vehicle propellant tank pressurization system, PU control system, vehicle acceleration and sloshing effects, and feed system-combustion coupled instabilities (3) Matching of the engine controls with the vehicle guidance system, including response of engin-start, cutoff, thrust level, and vector controls to vehicle guidance commands (4) Simulation of interaction between engine systems operation and vehicle dynamics. (This may involve closed-loop coupling of an analog simulation of vehicle guidance and trajectory characteristics with an engine system during hot firing)